Rachel Tsateri: Self-observation as a tool for professional development

Most teachers experience of observation starts on teacher training courses- CertTESOL, CELTA, DipTESOL and DELTA qualifications all involve several hours of observation and feedback.

Because of the high stakes involved in these observations, there can be a tendency for observation to carry negative affect and be seen as a necessary evil in the process of development.

This then carries over into our teaching careers with many teachers stressing out at annual observations, shying away from things like peer-observation and cringing when it comes to self-observation.

But observation is a powerful tool and if we learn how to do it well, it can be an invaluable instrument for our continuing professional development.

In this first post in our observation series. Rachel Tsateri explores the idea of self-observation and offers three practical ways to get started.

Rachel Tsateri of the Tefl Zone

One of the most useful and practical aspects of teacher training courses is having the opportunity to observe our peers. This usually serves two main purposes:

To learn from them or become aware of some techniques we could also use.

To give them feedback that can widen their perspective.

However, when we return to everyday teaching, we can’t always find people to observe us and give us constructive feedback. So, what do we do then? I say, we can rely on that one person who is always present in our classes - ourselves. By becoming an observer and examining our own teaching, we're making the first step towards becoming a reflective practitioner.

How do I do that?

Now some of you may think ‘but is this really easy? How can I evaluate my own teaching? Won't I be biased?

The answer is, if you take a scientific approach, it's easier than you think. First, we don't need to start with evaluating our actions. We need to start with collecting data. Ideally, we have recorded our lesson, so we can watch the video or listen back to the recording in order to get the information we need. The next step is to enter or categorise the data, e.g., fill in a table. We then need to ask the right questions to interpret the data. Finally, we can make informed evaluations and decisions.

Some tools

So, once we have collected the data and ideally, we can watch a recording or read the transcript of the lesson, we can use a range of self-observation tools to focus on and evaluate areas of our teaching.

we can either design our own self-observation tasks.

we can use readymade tasks created by ELT professionals, authors, or bloggers.

we can adapt these tasks to suit our needs.

Here are a couple of tools to get you started:

Teacher and students’ roles

Teacher Role Observation Form

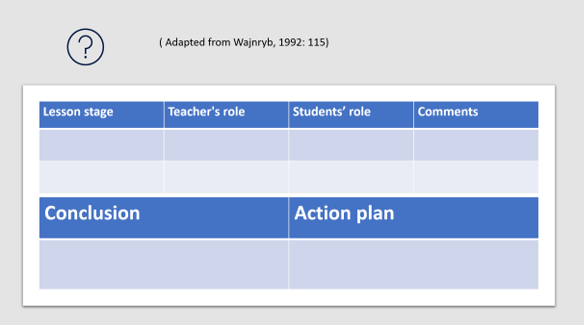

To understand what roles we assume during the lesson, and what we ask our students to do, we can use this task (adapted from Wajnryb’s book classroom observation tasks).

Here are the steps:

Watch/listen to the recording to identify the lesson stages and describe our teacher's role in each stage. Is it that of a facilitator, of a lecturer, of an assessor?

Then, notice what our students are doing and comment on their role (listeners, performers, problem solvers?).

We can later reflect on whether we felt our teacher's role was appropriate in the various stages of the lesson. For instance, perhaps we realized that during the grammar presentation stage we could have been the facilitator rather than the explainer, i.e., have our students get more actively involved (grammar detectives rather than passive listeners.)

Make an action plan: Did we become aware of something we could have done differently? Are we going to make a conscious effort to change that in next class? How?

Responding to learner errors

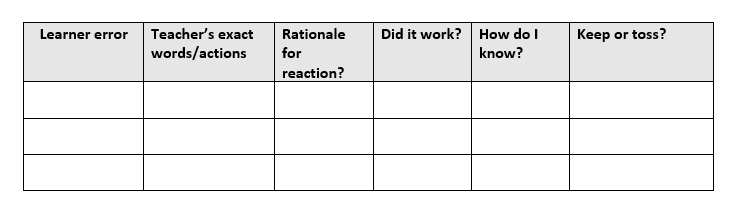

To identify and evaluate how we respond to learner errors, we can complete the following table:

Write down the error our learner produced. For example, the learner said ‘I will ask to my parents’.

We then write our exact words or actions. Did we correct on the spot? Did we use any gestures or facial expressions to draw attention to the error?

Next, try to ‘uncover’ the reason why we reacted that way. Perhaps we believe this is the best way to correct errors? Or maybe we felt that the specific student responds better when corrected in this way? Maybe we even base that on evidence from another lesson where this type of correction worked. Let’s find out whether it was a belief, intuition or previous evidence that informed our decision.

What did we notice? Did the technique work? This is a closed yes or no question.

Next, we ask ourselves an open question. How do we know? Think about the following. Did our student self-correct or understand the correction? Did the student use the correct version? Did they take notes or ask a follow-up question?

Finally, if we have identified different correction techniques, we can comment on whether we would keep using them or not and why.

Dissecting our instructions

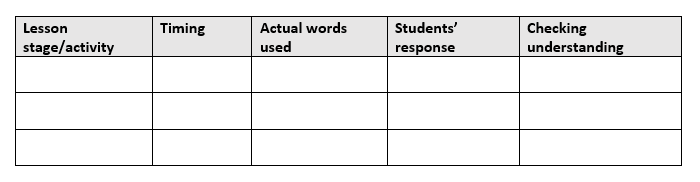

Both newly qualified and seasoned teachers sometimes have trouble giving clear instructions. Let’s have a look a look at a task that can help us reflect on our instructions.

If we have recorded our lesson, we can watch the recording and do the following:

Write the lesson phase/stage. Warmer? Controlled practice?

Time ourselves: how long did it take us to give instructions?

Transcribe what we say.

Is the language we're using simple and clear? If not, what changes do we need to make?

Did students understand what they needed to do?

How do we know? Did we ask instruction checking questions? Did we monitor to check they are doing the task?

I hope you find these tasks useful. If you'd like to read more ideas, have a look at Ruth Wajnryb’s book Classroom observation tasks: a resource book for language teachers and trainers.

What about you?

Do you use or design you own self-observation tasks?

Let us know in the comments!

References

Wajnryb, R., 1992. Classroom observation tasks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.